[February 20, 2014

[February 20, 2014

february 21, 2014 (theatlantic)

It has been only 21 days since Missouri began to execute convicted murderer Herbert Smulls some 13 minutes before the justices of the United States Supreme Court denied his final request for stay. And it is fair to say that the past three weeks in the state’s history of capital punishment have been marked by an unusual degree of chaos, especially for those Missouri officials who acted so hastily in the days leading up to Smulls’ death. A state that made the choice to take the offensive on the death penalty now finds itself on the defensive in virtually every way.

Whereas state officials once rushed toward executions—three in the past three months, each of which raised serious constitutional questions—now there is grave doubt about whether an execution scheduled for next Wednesday, or the one after that for that matter, will take place at all. Whereas state officials once boasted that they had a legal right to execute men even while federal judges were contemplating their stay requests now there are humble words of contrition from state lawyers toward an awakened and angry judiciary.

Now we know that the Chief Judge of the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, as well as the justices of the Supreme Court of the United States, are aware there are problems with how Missouri is executing these men. Now there are fresh new questions about the drug(s) to be used to accomplish this goal. Now there are concerns about the accuracy of the statements made by state officials in defending their extraordinary conduct. Herbert Smulls may be dead and gone but his case and his cause continue to hang over this state like a ghost.

The Supreme Court Wants Answers

Missouri’s problems started almost immediately after Smulls was executed on January 29. On January 30, the Associated Press published a story titled: “Lawyers: Mo. Moving Too Quickly on Executions” in which it was disclosed, for the first time to a national audience, that state officials were executing prisoners before their appeals were exhausted. On February 1, we posted a piece here at The Atlantic titled: “Missouri Executed This Man While His Appeals Was Pending in Court,” in which we published emails from Smulls’ attorneys to Missouri officials showing that the state was aware that Smulls’ appeal was pending at the Supreme Court at the very moment he was being injected with lethal drugs.

Clearly, the justices in Washington were paying close attention to what Missouri had done (killed Smulls) and not done (waited for the justices to tell them they could). On February 3, five days after Smulls’ execution, the Clerk of the Court wrote to Missouri officials directing them to file a second response to a petition for certiorari that had been filed on behalf of Smulls and several other death row inmates (who are still alive). The request demonstrated, at the least, that the Court did not consider Smulls’ final appeal to be frivolous. Here is the link to that letter. Missouri’s response is due March 5. I am curious to know whether state officials reveal any regret for the timing of the Smulls’ execution.

A Roiling Hearing

One week after Missouri received that letter from the Supreme Court, state officials appeared at a legislative hearing to discuss and defend Missouri’s execution protocols. David Hansen, a state assistant attorney general, spoke at length about the Smulls’ execution. There was no stay in effect at the time of the condemned man’s execution, Hansen told lawmakers, and the controversy over premature executions was caused not by overzealous state officials but rather by “death row attorneys” who, he said, “have developed a legitimate and very deliberate strategy to ensure that there is always a stay motion pending during the course of the [death] warrant which is a de facto repeal of the death penalty.”

Here is the link to much of Hansen’s testimony. It was confident. It was defiant. And in several material respects, it was inaccurate. For example, Hansen quoted James Liebman, the distinguished professor at Columbia Law School, for the proposition that what Missouri has been doing is also being done in other states. But Liebman did not say that and was so dismayed by the misuse of his words that he submitted a letter late Tuesday night to Missouri’s lawmakers seeking to clarify the record. Here is the link to Liebman’s letter. And here is the essence of his position on the inappropriateness of Missouri’s current execution protocol:

I pointed out that the Supreme Court has occasionally issued orders in capital cases saying it will no longer entertain papers from a particular capital prisoner, having found that previous papers filed were frivolous. I pointed out that, if Missouri believed that this same point had been reached in Mr. Smulls’ case—a conclusion that Mr. Smulls and his attorneys strongly disputed—it would not be appropriate for one adversary to resolve that matter unilaterally over the objection of the other.

Instead, Mr. Hansen’s office should have formally asked the Supreme Court to deny Mr. Smulls’ pending papers and to refuse to accept further papers from him, thus allowing the state to proceed with an execution without fear that the legal basis for that solemn and irreversible action was in doubt. Only then would the crucial contested matter of law and fact have been resolved, not unilaterally by one party to the dispute, but by the decision of a neutral court of law.

This was not the only problem with Hansen’s testimony. Joseph W. Luby, an attorney for Smulls and other death row inmates in the state, also felt compelled to write a letter to Missouri lawmakers seeking to correct the record that Hansen had created. Not only had Hansen mischaracterized the procedural posture of the three cases in which Missouri had executed inmates before their appeals were exhausted, Luby wrote, but state officials were engaged in a pattern and practice of not even responding to opposing counsel in the final hours and minutes before executions. Here is the link to Luby’s letter. He didn’t say it but I will: This is inappropriate and perhaps unethical conduct by of state lawyers.

Another Federal Judge Calls Out Missouri

Two days after that hearing, on February 12, the Chief Judge of the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, William Jay Riley, who repeatedly had voted against Smulls, interrupted oral argument in an unrelated death penalty case to tell a lawyer for the State Attorney’s General office that the federal appeals panel did not in any event appreciate Missouri officials executing men before the courts had concluded their judicial review. Specifically, Chief Judge Riley said:

I might just tell you this. I’ll probably regret saying this later, but I think it was the execution of Nicklasson, but the State of Missouri executed somebody which they probably had the right to do, right in the middle of our petition for rehearing voting. And I just wanted you to take back the word that… some of the members of the Court did not appreciate that. That we were right in the middle of that…

And I think you have probably heard that some people have written on it. But we were moving as fast as we can and, as Chief Judge, I was pushing to get everything done in time. But I think you need to be a little more patient.

The “Nicklasson execution” to which the Chief Judge referred, took place on December 12 and it prompted from 8th U.S. Circuit Court Judge Kermit Bye a remarkable dissent. “I feel obliged to say something,’ Judge Bye wrote at the time, “because I am alarmed that Missouri proceeded with its execution of Allen Nicklasson before this court had even finished voting on Nicklasson’s request for a stay.” He continued:

In my near fourteen years on the bench, this is the first time I can recall this happening. By proceeding with Nicklasson’s execution before our court had completed voting on his petition for rehearing en banc, Missouri violated the spirit, if not the letter, of the long litany of cases warning Missouri to stay executions while federal review of an inmate’s constitutional challenge is still pending.”

Here are the links to Judge Bye’s first and second dissents in these premature execution cases.

The Drug Supplier Bags Out

Seven days after Chief Judge Riley’s admonition, this past Monday, came the next bad thing to happen to Missouri officials in their quest to expedite the implementation of the death penalty in their state. Under legal pressure from death row inmate Michael Taylor, the compounding pharmacy that was poised to supply the drug (pentobarbital) the state wanted to use to execute him next week backed out of its commitment to provide the drug. The Apothecary Shoppe, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, announced that it would not give the Missouri Department of Corrections the pentobarbital it had compounded and that it had not previously given state officials the drug for Taylor’s execution.

Missouri immediately reacted to this unexpected news by declaring that it would be able to proceed anyway with Taylor’s execution, now scheduled for the 26th, without materially changing its lethal injection protocols. Late Wednesday, state officials informed Taylor’s lawyers that they have obtained pentobarbital from another, unidentified supplier. “There is no reason to believe that the execution will not, like previous Missouri executions using pentobarbital, be rapid and painless,” state attorneys wrote in a motion filed with a federal trial judge in Missouri opposing a stay request by Taylor. Here is the link to Missouri’s filing.

A New Challenge to Missouri’s Lethal Injection Rules

The confusion over precisely how Missouri intends to execute Taylor generated on Tuesday another big headache for state officials– a substantial new request for a stay of execution in Taylor’s case. Here is the link to that motion and here is how defense attorneys summarize their argument:

Missouri has identified no lawful means of executing Taylor next week. Any pentobarbital Missouri previously acquired is now expired. Though Missouri has indicated it has midazolam and hydromorphone, its execution protocol does not permit administration of those drugs; even if it did, Taylor would warrant a stay because those drugs have already inflicted unconstitutional pain and suffering in an execution and the states using them have thus temporarily halted executions.

In any event, switching the protocol or the pentobartibal supplier now – a week before the scheduled execution – would violate Taylor’s right to due process of law.

Taylor’s lawyers made those arguments before they learned that Missouri had reportedly acquired a new supply of pentobarbital. State lawyers would say only in their court filing Wednesday that “Missouri has now arranged with a pharmacy, that is not the pharmacy Taylor threatened and sued, to supply pentobarbital for Taylor’s execution.” In their response Thursday, the link to which may be found here, Taylor’s lawyers wrote this:

Utterly nothing is known about this pharmacy. Has it been cited for

violating federal and state laws more or less often than the previous pharmacy? Does it also send its drugs, to be tested for purity and sterility, to a laboratory that approved a batch of tainted steroids that killed over 60 people? For that matter, does the pharmacy test its drugs at all?

If Missouri has its way, it will not tell Taylor anything more about the drug officials seek to use to execute him next week. It will argue that the conduct of its officials should be presumed to be lawful, and proper, and designed to respect the constitutional rights of the condemned. A few weeks ago, we know, the federal courts were willing to accept these arguments and to allow these dubious executions to proceed. Now I’m not so sure. No matter what the trial judge decides on Taylor’s stay request, this dispute is going first to the 8th Circuit and then to the Supreme Court. Will those appellate judges be motivated to remind Missouri who gets the final say on executions in this nation?

february 20, 2014 (theguardian)

The state corrections official who stands beside condemned inmates as they take their last breaths in Florida’s death chamber recently pulled back the veil on what has largely been a very secretive execution process.

The testimony was given during a 11 February hearing in a lawsuit involving Paul Howell, a death row inmate scheduled to die by lethal injection 26 February. Howell is appealing his execution; his lawyers say the first of the injected drugs, midazolam, isn’t effective at preventing the pain of the subsequent drugs.

The Florida supreme court specifically asked the circuit court in Leon County to determine the efficacy of the so called “consciousness check” given to inmates by the execution team leader.

The testimony is notable because it shows that the Department of Corrections has changed its procedures since the state started using a new cocktail of lethal injection drugs. A shortage of execution drugs around the country is becoming worse as more pharmacies conclude that supplying the lethal chemicals is not worth the bad publicity or legal and ethical risks.

Timothy Cannon, who is the assistant secretary of the Florida Department of Corrections and the team leader present at every execution, told a Leon County court that an additional inmate “consciousness check” is now given due to news media reports and other testimony stemming from the 15 October execution of William Happ.

Happ was the first inmate to receive the new lethal injection drug trio. An Associated Press reporter who had covered executions using the old drug cocktail wrote that Happ acted differently during the execution than those executed before him. It appeared Happ remained conscious longer and made more body movements after losing consciousness.

Cannon said in his testimony that during Happ’s execution and the ones that came before it, he did two “consciousness checks” based on what he learned at training at the Federal Bureau of Prisons in Indiana – a “shake and shout”, where he vigorously shakes the inmate’s shoulders and calls his name loudly, and also strokes the inmate’s eyelashes and eyelid.

After Happ’s execution, Cannon said the department decided to institute a “trapezoid pinch”, where he squeezes the muscle between an inmate’s neck and shoulder.

It was added “to ensure we were taking every precaution we could possibly do to ensure the person was, in fact, unconscious”, Cannon said. “To make sure that this process was humane and dignified”.

Lawyers for Howell say that they are concerned that the midazolam does not produce a deep enough level of unconsciousness to prevent the inmate from feeling the pain of the second and third injection and causes a death that makes the inmate feel as though he is being buried alive.

“Beyond just the fact that constitution requires a humane death, if we decided that we wanted perpetrators of crime to die in the same way that their victims did then we would rape rapists. And we don’t rape rapists,” said Sonya Rudenstine, a Gainesville attorney who represents Howell.

“We should not be engaging of the behavior that we have said to abhor. If we are going to kill people, we have to do it humanely. It’s often said the inmate doesn’t suffer nearly as much as the victim, and I believe that’s what keeps us civilized and humane.”

Corrections spokeswoman Jessica Cary said on Wednesday that the department “remains committed to doing everything it can to ensure a humane and dignified lethal injection process”.

Cannon explained in his testimony that each execution team member “has to serve in the role of the condemned during training at some point”.

“We’ve changed several aspects of just the comfort level for the inmate while lying on the gurney,” he said. “Maybe we put sponges under the hand or padding under the hands to make it more comfortable, changed the pillow, the angle of things, just to try to make it a little more comfortable, more humane and more dignified as we move along.”

He said an inmate is first injected with two syringes of midazolam and a syringe of “flush”, a saline solution to get the drug into the body. Midazolam is a sedative.

Once the three syringes have been administered from an anonymous team of pharmacists and doctors in a back room, Cannon does the consciousness checks.

Meanwhile, the team in the back room watches the inmate’s face on a screen, which is captured by a video camera in the death chamber. The inmate is also hooked up to a heart monitor, Cannon said.

There are two executioners in the back room – the ones who deploy the drugs – along with an assistant team leader, three medical professionals, an independent monitor from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement and two corrections employees who maintain an open line to the governor’s office.

If the team determines that the inmate is unconscious, the other two lethal drugs are administered.

february 13, 2014

A federal judge late Wednesday temporarily blocked an Oklahoma compounding pharmacy from selling a drug to the Missouri Department of Corrections for use in a Feb. 26 execution.

The temporary restraining order was issued in connection with a lawsuit in United States District Court in Tulsa filed by a Missouri death row inmate, Michael Taylor, whose lawyers say the state contracts with the Apothecary Shoppe in Tulsa for the drug.

The lawsuit argued that recent executions involving the drug, compounded pentobarbital, indicate it will probably cause “severe, unnecessary, lingering and ultimately inhumane pain.”

The state has not revealed the name of the pharmacy, and the Tulsa pharmacy has not said whether it is the supplier. The judge, Terence Kern, set a hearing for Tuesday.

(Source:NYT)

february 12, 2014

UPDATE: Juan Carlos Chavez was executed at 8:17 p.m., according to the governor’s office.

UPDATE 6.30 PM

The execution of Juan Carlos Chavez, the South Miami-Dade farmhand who raped and murdered 9-year-old Jimmy Ryce in 1995, was temporarily delayed Wednesday evening because of last-minute legal wrangling.

A spokeswoman for the office of Gov. Rick Scott said the state, as of 6:30 p.m., was still awaiting a final go-ahead from the U.S. Supreme Court.

UPDATE 3.55 pm

For his last meal, Chavez requested ribeye steak; French fries; a fruit mixture of mangoes, bananas and papaya; strawberry ice cream; and mango juice. He ate and drank all of it, according to Department of Corrections spokeswoman Jessica Cary.

Chavez had no visitors Wednesday except for a Catholic spiritual adviser. Cary said his demeanor was calm.

————————————————————————–

For Pat Diaz, retracing the steps of a tragedy is not easy.

“That’s the bus stop,” Diaz says, pointing at a street corner in the area near Homestead known as the Redland.

The former Miami-Dade Police homicide detective led the search for a missing boy named Jimmy Ryce back in 1995.

“When you have a missing 9-year-old, you want to believe, you always have the hope that you’ll find the child,” Diaz said, reminiscing about the case that would haunt his career.

To this day, the street sign at the corner is a memorial to the little boy who never grew up, decorated with flowers and pictures of Jimmy. A man named Juan Carlos Chavez took Jimmy, a case that struck fear into the hearts of parents everywhere. Detective Diaz heard the details when Chavez confessed.

“He tells us he rolls down his window, points the gun at him and says get in the trunk, Jimmy crosses the street and gets in the trunk with him, and basically this is where it happened,” Diaz said, standing at the spot at which Chavez abducted the boy. “Jimmy was probably 250 yards from his house, that’s how close he was to his house.”

Volunteers passed out flyers, joined police in searching the area, and it was all too late. Chavez had already abducted, tortured, and killed Jimmy in his trailer.

“It’s the parent’s worst nightmare,” said Michael Band, a Miami attorney who, in 1995, was the prosecutor on the case.

Band won the first-degree murder conviction and a death sentence for Chavez, who is scheduled to be executed Wednesday.

But it wasn’t easy, Band says. There was tremendous pressure from the community, the trial had to be moved to Orlando to seat an impartial jury, and he had to control his own emotions.

“You don’t remove yourself, you try to be as rational as one can be but you think about things like that, you think, that could’ve been my kid, could’ve been your kid,” Band said.

Chavez was on the way to death row, but the pain only got worse for the victim’s father, Don Ryce: Over the years he lost everyone except his son, Ted Ryce. After Jimmy’s murder, the stress and depression hung over the Ryce family. A heart attack killed Don Ryce’s wife, Claudine Ryce, in 2009. His daughter committed suicide, still despondent over Jimmy’s death.

“If there was ever anyone in the world who deserved to die it’s the man who did that,” Don Ryce said last month, speaking after the governor signed the death warrant for Chavez.

“I think, sadly, the statistics are that predators are not going to be deterred because Juan Carlos Chavez gets executed,” Band said.

That doesn’t mean Band has second thoughts about asking for the death penalty. He agrees that Chavez got what he deserved. Band says the verdict was professionally satisfying, but there’s a hole in his heart when he thinks of Don Ryce.

“He still goes home without Jimmy,” Band said, and the execution won’t change that awful reality. (nbcmiami)

February 11, 2014

Juan Carlos Chavez

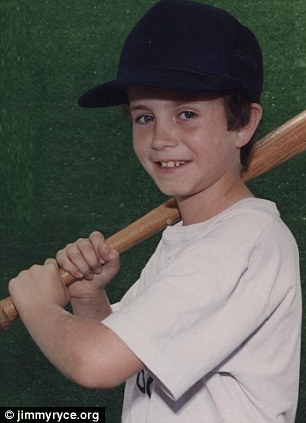

Jimmy Rice

Jimmy Rice

MIAMI (CBSMiami) — “It’s been a long, long time coming,” said the father of Jimmy Ryce, upon learning that Wednesday, February 12th is the day the man who kidnapped, raped, murdered and dismembered his 9-year-old son, will be put to death.

It was September 11, 1995 when Jimmy Ryce disappeared without a trace when he got off his school bus near his home in The Redland.

Juan Carlos Chavez, 46, was convicted of the heinous crime three years later.

It was a trial that captivated South Florida and the rest of the nation.

Chavez was charged with the crime three months after Jimmy vanished. Chavez confessed but years would pass before he came to trial. The delay tormented Jimmy’s parents.

“There is no constitutional right to delay a trial until the victim’s families die of old age,” said Jimmy’s father Don Ryce in May of 1998.

Chavez did eventually go before a jury in Orlando. The trial was moved there because of intense media scrutiny. The Ryce family came to the trial every day, including Jimmy’s sister Martha.

“And I’m here to represent my family, and Jimmy, because he can’t be here,” said Martha in September of 1998.

Lead prosecutor Catherine Vogel told of Chavez confessing to snatching Jimmy Ryce from the side of the road, raping and shooting him in a remote trailer, and then using a wicked looking bush hook to dismember the boy’s body.

“He took the tool, he chopped the body into about four different pieces,” said Vogel during the 1998 trial.

Chavez sealed the remains with concrete in plastic planters.

For then prosecutor Vogel, now Monroe County’s State Attorney, they are images she will never forget.

“We had to excavate those planters, we had to dig through the concrete to find poor little Jimmy Ryce’s body that had been dismembered,” said Vogel.

Ranch owner Susan Scheinhaus testified how she found Jimmy’s book bag and homework in a travel camper that Chavez lived in which was located on her property where he worked as a farm hand. But the defense dropped a bombshell.

“The detectives were telling me what I should and should not write,” said Chavez through a translator at the trial.

Chavez recanted his confession and claimed his employer’s son killed Jimmy.

The Ryce’s watched outraged at the defense ploy.

“Their dream is to exchange high fives over Jimmy’s grave, while they set their client loose to rape and murder another child,” said an angry Don Ryce during the trial.

But former homicide detective Felix Jimenez, who is now with the Inspector General’s office, took Chavez’s confession. He said Chavez first told a series of lies including a tale of accidentally running over Jimmy and putting his body in a canal that divers searched for hours before Chavez finally came clean.

“He admitted in detail to everything that he did,” said Jimenez. “His confession was so detailed, that only the killer would know.”

For instance, police didn’t know until Chavez told them that Jimmy was killed in the filthy, falling down trailer.

“When we went there and we looked, and we found Jimmy Ryce’s blood exactly where he said he shot him, then we knew we had gotten to the truth,” said Vogel.

A gun found in Chavez’s camper was an exact ballistics match for the bullet that killed Jimmy.

The jury convicted Chavez on all counts in less than an hour.

“Had he gotten away with it, he would have killed again and again and again,” said Michael Band, the man who prosecuted Chavez. Band is now a private defense attorney.

On November 23, 1998, Chavez was sentenced to death.

Judge Marc Schumacher sentenced Chavez to die in old sparky, the electric chair. But the appeals dragged on for years.

At a hearing in January 2007, his mother said, “You know, it’s been over eleven years since Jimmy was killed, and he was only nine years old. So he’s been dead longer than he lived.” Jimmy would have been 21 years old at that hearing.

Governor Rick Scott finally signed the death warrant for Chavez in January.

Claudine Ryce didn’t live to see it. She died from coronary disease, a broken heart, in 2009.

Jimmy’s sister Martha took her own life last year at the age of 35.

When Don Ryce learned of the Chavez’s death warrant last month, he wept. His son Ted is his only remaining family.

“We’ve suffered a terrible loss,” said an emotional Don Ryce. “A loss you don’t wish on anyone.”

Monday, February 10th, Chavez was denied a stay of execution by the U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals. It’s one of the final appeals left for Juan Carlos Chavez before his scheduled execution on Wednesday evening. click here opinion.pdf

february 7, 2014

Gov. John Kasich has postponed the scheduled March 19 execution of Gregory Lott because of lingering concerns about the drugs used in the lethal injection of Dennis McGuire last month.

Kasich this afternoon used his executive clemency power to move Lott’s execution to Nov. 19.

While the governor did not cite a reason, Kasich spokesman Rob Nichols said he wanted to give the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction time to complete its internal review of McGuire’s Jan. 16 execution. “Gregory Lott committed a heinous crime for which he will be executed,” Nichols said.

During his Jan. 16 execution, McGuire, 53, gasped, choked and clenched his fists, all the while appearing to be unconscious, for at least 10 minutes after the lethal drugs – 10 mg of midazolam, a sedative, and 40 mg of hydromorphone, a morphine derivative – flowed into his body. The drugs had never been used together for an execution.

Attorneys for Lott, 51, are challenging his execution, complaining the drugs could cause “unnecessary pain and suffering” in violation of the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. A hearing has been scheduled for Feb. 19 in the U.S. District Judge Gregory L. Frost’s court.

Lott, 51, was convicted and sentenced to death for killing John McGrath, 82, by setting him on fire in his Cleveland-area home in 1986. McGrath survived in a hospital for 11 days before dying. Lott came close to execution in 2004, but the U.S. Supreme Court blocked it.

Kevin Werner, executive director of Ohioans to Stop Executions, praised Kasich for showing “leadership and careful consideration” by issuing a temporary reprieve.

february 7,2014

The Florida Supreme Court on Thursday ordered a review of the new drug used in the state’s lethal injection cocktail in the case of Paul Augustus Howell, a Death Row inmate scheduled for execution Feb. 26.

Justices ordered a circuit court to hold an evidentiary hearing on whether substitution of the drug midazolam violates the constitutional protections against cruel and unusual punishment by the government.

Howell’s lawyers argued in briefs filed Tuesday that midazolam, the first of the three drug-cocktail that induces unconsciousness, paralysis and cardiac arrest, is problematic because it will not anesthetize him and would leave him “unable to communicate his agony” when the other drugs are administered.

The justices rejected an appeal about the new drug in a previous case, but in a four-page order issued Thursday said that an expert’s report submitted by Howell “has raised a factual dispute, not conclusively refuted, as to whether the use of midazolam, in conjunction with his medical history and mental conditions, will subject him to a ‘substantial risk of serious harm.’ ”

The court also ordered the Department of Corrections to produce correspondence and documents from the manufacturer of midazolam concerning the drug’s use in executions, “including those addressing any safety and efficacy issues.”

The high court ordered the 2nd Judicial Circuit in Jefferson County, where Howell was originally tried and convicted of the murder of a highway patrol trooper in 1992, to hold a hearing and enter an order on the issue by 2 p.m. Wednesday.

In September, the Florida Department of Corrections substituted midazolam for the barbiturate pentobarbital as the first of the three-drug lethal injection “protocol.” Florida and other states switched to the new drug because the manufacturer of pentobarbital stopped selling it for use in executions.

The second drug, vecuronium bromide, renders muscle, including the diaphragm, unable to contract, making it impossible to breathe.

If not completely anesthetized when that drug is administered, the condemned would “experience the physical and psychological agony of suffocation,” Howell’s lawyers argued in briefs filed Tuesday.

The new drug protocol has been used four times since its adoption in September, but Howell’s lawyers argued that three of those executed were not fully anesthetized before the other drugs were administered.

The Supreme Court on Thursday also ordered the court to consider testimony from University of Miami anesthesiologist David Lubarsky regarding problems with the state’s protocol for making sure that inmates are unconscious. According to Lubarsky, the state is not waiting long enough between injections for the anesthetic to take effect. Lubarsky also testified the drug poses a significant risk for “paradoxical reactions” for Howell because he has mental health disorders and possible brain injuries.

Howell was scheduled to be executed last year but a federal appeals court issued a stay the day before he was slated to die. The stay was lifted in November, and Gov. Rick Scott rescheduled his execution for Feb. 26.

Americans have developed a nearly insatiable appetite for morbid details about crime, as any number of docudramas, Netflix series and Hollywood movies attest.

There is 1 notable exception: executions. Here, we’d just rather not know too much about current practices. Better to just think of prisoners quietly going to sleep, permanently.

The blind eye we turn to techniques of execution is giving cover to disturbing changes with lethal injection. The drugs that have traditionally been used to create the deadly “cocktail” administered to the condemned are becoming harder to get. Major manufacturers are declining to supply them for executions, and that has led states to seek other options.

That raises questions about how effective the lethal drugs will be. At least 1 execution appears to have been botched. In January, an inmate in Ohio was seen gasping for more than 10 minutes during his execution. He took 25 minutes to die. The state had infused him with a new cocktail of drugs not previously used in executions.

States have been forced to turn to relatively lightly regulated “compounding pharmacies,” companies that manufacture drugs usually for specific patient uses. And they’d rather you not ask for details. Death row inmates and their attorneys, on the other hand, are keenly interested in how an approaching execution is going to be carried out. Will it be humane and painless or cruel and unusual?

Lawyers for Herbert Smulls, a convicted murderer in Missouri, challenged the compound drug he was due to be given, but the Supreme Court overturned his stay of execution. A district court had ruled that Missouri had made it “impossible” for Smulls “to discover the information necessary to meet his burden.” In other words, he was condemned to die and there was nothing that attorneys could do because of the secrecy.

Smulls was executed Wednesday.

Missouri, which has put 3 men to death in 3 months, continues shrouding significant details about where the drugs are manufactured and tested. In December, a judge at the 8th U.S. Circuit of Appeals wrote a scathing ruling terming Missouri’s actions as “using shadow pharmacies hidden behind the hangman’s hood.”

States have long taken measures to protect the identities of guards and medical personnel directly involved with carrying out death penalty convictions. That is a sensible protection. But Missouri claims the pharmacy and the testing lab providing the drugs are also part of the unnamed “execution team.”

That’s a stretch. And the reasoning is less about protecting the firm and more about protecting the state’s death penalty from scrutiny.

The states really are in a bind. European manufacturers no longer want to be involved in the U.S. market for killing people. So they have cut off exports of their products to U.S. prisons.

First, sodium thiopental, a key to a long-used lethal injection cocktail became unavailable. Next, the anesthetic propofol was no longer available. At one point, Missouri was in a rush to use up its supply before the supply reached its expiration date.

Next, the state decided to switch to pentobarbital. So, along with many of the more than 30 states that have the death penalty, Missouri is jumping to find new drugs, chasing down new ways to manufacture them.

Information emerged that at least some of Missouri’s lethal drug supply was tested by an Oklahoma analytical lab that had approved medicine from a Massachusetts pharmacy responsible for a meningitis outbreak that killed 64 people.

For those who glibly see no problem here, remember that the U.S. Constitution protects its citizens from “cruel and unusual punishment.” But attorneys for death row inmates are finding they can’t legally test whether a new compounded drug meets that standard because key information is being withheld. Besides, we citizens have a right to know how the death penalty is carried out.

All of this adds to the growing case against the death penalty, showing it as a costly and irrational part of the criminal justice system. We know the threat of it is not a deterrent. We know it is far more costly to litigate than seeking sentences for life with no parole. We know extensive appeals are excruciating for the families of murder victims. And we know that some of society’s most unrepentant, violent killers somehow escape it.

And now we’ve got states going to extremes to find the drugs – and hide information about how they got then – just to continue the killing.

ABOUT THE WRITER Mary Sanchez is an opinion-page columnist for The Kansas City Star

(source: Fresno Bee)

Aug. 03, 2013

It is welcome news that the Texas prison system’s supply of the drug used for execution is about to expire and the state may have trouble replenishing its stash of pentobarbital.

Even if this problem for the state isn’t long-lasting, it gives me a ray of hope that one day lethal injection may go the way of “Old Sparky,” the electric chair used in Texas for 40 years.

When the state took charge of executions (previously relegated to the counties) in 1923, it decided that electrocution, rather than hanging, would be the method used to kill inmates sentenced to death.

Between 1924 and 1964, Texas electrocuted 361 people in that chair before the Supreme Court halted capital punishment for a while.

After reinstatement of the death penalty by the high court, Texas decided to adopt lethal injection for execution, retiring Old Sparky — now housed at the Texas Prison Museum in Huntsville — and replacing it with a gurney.

Charlie Brooks of Fort Worth became the first person executed in the country by injection. He was given a three-drug cocktail of sodium thiopental, pancuronium bromide and potassium chloride, a combination the state used until two years ago.

Since Brooks died, Texas has put to death 502 other prisoners (11 this year), far more than any other state in the country. Virginia has the second-highest number of executions with 110.

Although the state doesn’t divulge who supplies its drugs for execution, The Guardian newspaper reported in 2010 that British companies were secretly supplying some American prisons with drugs used for lethal injections.

Pressure was put on those companies and on government officials to stop exporting the drugs for capital punishment purposes.

In 2011, the maker of sodium thiopental stopped producing the drug under pressure from anti-death penalty supporters, and in 2012 the state could not get access to pancuronium bromide, according to a report by the Houston Chronicle.

Since that time Texas’ lethal injections have been of a single drug, pentobarbital, which is commonly used for euthanizing animals.

The state’s supply of the drug expires in September, when it has two more executions scheduled. Prison officials have not said if those executions, or three others set for this year, will be delayed.

The question is, what will the state do if the pentobarbital becomes permanently unavailable?

Michael Graczyk of The Associated Press reported that some states are “turning to compounding pharmacies, which make customized drugs that are not scrutinized by the Federal Drug Administration, to obtain a lethal drug for execution use.”

At least one state is considering returning to the gas chamber, but I can’t imagine Texas considering another method besides lethal injection.

We can’t go back to the electric chair or hanging, and the public certainly wouldn’t stand for instituting firing squads or gas as a means killing people.

So it seems we are stuck with the needle and some drug.

The fact that pressure on drug manufacturers has had some impact on holding up executions means death penalty opponents now have another weapon in their fight against capital punishment.

While they’ll still fight legislatively and through the courts, it would be a rewarding victory if they can continue to convince drug companies not to supply these death chambers with doses of lethal pharmaceuticals.

It would be a different kind of “war on drugs,” but it would be one worth waging.

Tubing and straps used in the execution of Brooks in 1982 are now in the museum with Old Sparky.

Perhaps it won’t be too long before we can retire the gurney for exhibit purposes only and close Texas’ death chamber for good.